Last update: 3 August 2015

Introduction

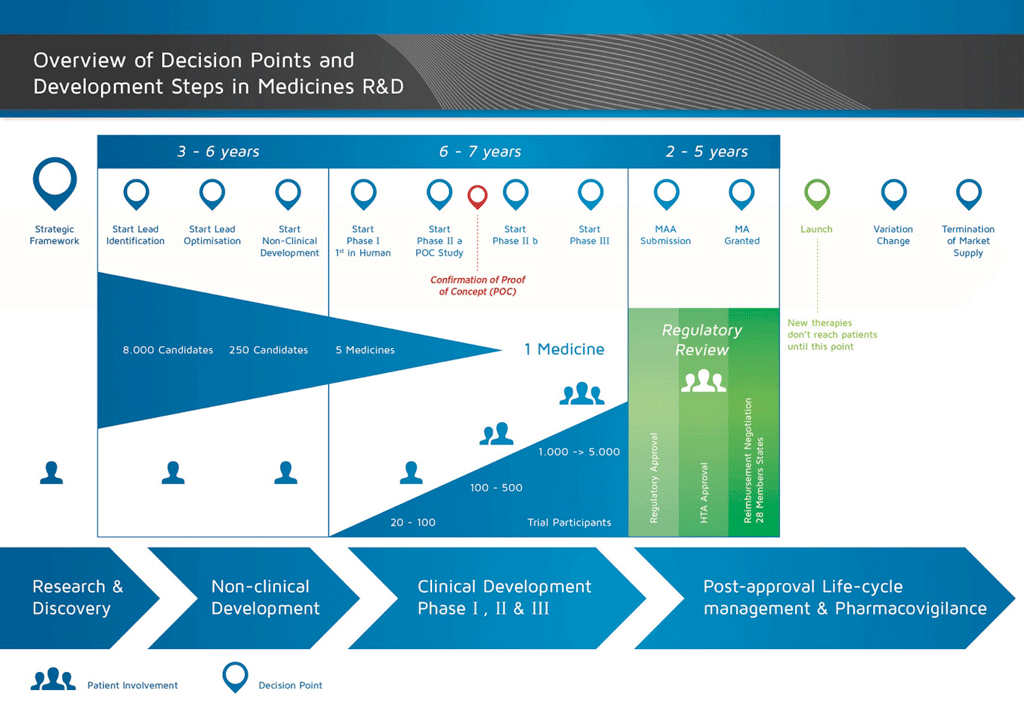

It takes over 12 years and on average costs over €1 billion to do all the research and development necessary before a new medicine is available for patients to use.

Medicines development is a high-risk venture. The majority of substances (around 98%) being developed do not make it to the market as new medicines. This is mostly because when you look at the benefits and risks (negative side effects) found during development do not compare well with medicines that are already available to patients.

The development of a new medicine can be divided into 10 different steps. The following article covers Step 6: Proof of mechanism – Phase I clinical studies.

- It takes well over 10 years of careful planning and research for a medicine to go from molecule to a marketable treatment.

Step 6: Proof of mechanism – Phase I clinical studies

The decision to start the first clinical study is a major one. As a candidate compound continues through the development process, the number, cost, and complexity of the activities involved in the process all increase.

Before starting a clinical study, a Clinical Trial Application (CTA) must be submitted. The CTA must include the following important documents:

- An Investigational Medicinal Product Dossier (IMPD), including ADME and studies to observe effect (on the target), the toxicology safety information, and information on how the medicine is manufactured.

- The Study Protocol, describing the details of performing the study and evaluating the results

- The Investigator’s Brochure (IB), providing a summary of the information that allows the doctors who run the study (the investigators) to understand how the study medicine works in the body (the pharmacology). This allows the investigators to explain the study to the volunteer or patient and to obtain informed consent (see below).

The CTA must be submitted to the National Competent Authority (NCA) for approval. During the process, an opinion from the ethics committee is also sought.

Safety is the top priority; therefore, a study in humans cannot start until the Internal Company Review Committee, the External Ethics Committee and the External Regulatory Authority have given their approval.

Volunteer studies (also called Exploratory Studies, Proof of Mechanism Studies, or Phase I studies)

This study allows the doctors and scientists to see if the medicine is safe in humans. It also looks at whether the medicine behaves in humans in the same way that it behaved in animals. These studies provide information on the way that the medicine works – called the ‘mechanism of action’. These studies also aim to discover any secondary effects of the medicine.

About 20 -100 volunteers are included in the Phase 1 of the clinical studies. These studies are usually carried out in special Phase 1 units where the volunteers are recruited and the studies are run. The doctors who carry out these studies are called investigators and they are qualified to conduct clinical trials in order to determine the outcome of the study.

The first clinical study is usually carried out in healthy male volunteers. The details of the clinical study must be described in the Study Protocol, and must include:

- the background of the disease (the unmet need),

- the non-clinical information,

- the details of the clinical study (what exactly will be done and when), and

- how the information will be used and analysed.

All the information coming from the study is collected in a document called the Case Record Form (CRF).

Here, too, there are a large number of guidelines and regulations known as Good Clinical Practice (GCP) to protect the safety of the participants in the study.

The Study Protocol also has a section on ‘statistics’, which are the statistical tests used to analyse the results. These directions must be decided before the study starts, so it is known how information will be obtained and used once the study ends.

Two very important elements are:

- Informed consent (ensuring that the participants understand what is going to be done and agree to be part of the study), and

- Ethics Committee review and opinion.

The Ethics Committee is an independent group, usually consisting of doctors, scientists, nurses, and non-experts (‘lay members’). They review the Study Protocol (especially the informed consent form) and ensure that they comply with the ethical regulations of the committee before the study is carried out. Safety has the highest priority; in order to ensure the safety of the participants in a clinical study, internal company approval, external Ethics Committee positive opinion, and National Competent Authority (NCA) approval is required. The rules for Phase I studies became even stricter after a rare case in 2006 in which volunteers suffered serious side effects after using an immunomodulatory medicine to treat B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and rheumatoid arthritis.

As safety is a priority, the first clinical study starts with a very low dose of the medicine:

- A single dose of the medicine is used for each volunteer.

- Once it has been shown that there are no safety concerns with this first dose, the study can continue with a slightly higher dose.

- The dose will then be further increased (‘ascending dose’) until the maximum dose allowed for the study has been reached.

This is described in the Study Protocol.

The study results can then be analysed and all the safety measurements can be assessed. This includes the:

- pharmacokinetics – what the body does to the medicine. The blood levels of the medicine can be measured – to determine the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME)

- pharmacodynamics – what the medicine does to the body (the ‘effect’). For example, the study might measure the effect of a medicine on certain blood cells.

This type of study is known as a Single Ascending Dose (SAD) study. This is usually followed by a Multiple Ascending Dose (MAD) study which, as the name suggests, involves multiple doses per volunteer.

Apart from the SAD and MAD studies, other Phase I studies are also needed. For example:

- to look at the effect of food

- to look at the effect of other medicines given at the same time

- to look at the effect of other diseases which might mean a different dose of the medicine is needed (for example in patients with kidney disease).

References

- Edwards, L., Fox, A., & Stonier, P. (Eds.). (2010). Principles and practice of pharmaceutical medicine (3rd ed.). Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Attachments

- Fact Sheet: Proof of mechanism studies

Size: 106,807 bytes, Format: .docx

This fact sheet covers Phase I clinical or ‘proof of mechanism’ studies, the first studies that test a candidate compound in humans.

- Presentation: The basic principles of medicine discovery and development

Size: 918,164 bytes, Format: .pptx

The basic principles of medicine discovery and development. It takes over 12 years and over €1 billion to do all the research and development necessary before a new medicine is available for patients to use. This presentation details the process from discovery to release of a new medicine onto the market and beyond.

A2-1.02.5-v1.1