Last update: 11 July 2023

Published and available for citation: Klingmann I, Heckenberg A, Warner K, Haerry D, Hunter A, May M and See W (2018) EUPATI and Patients in Medicines Research and Development: Guidance for Patient Involvement in Ethical Review of Clinical Trials. Front. Med. 5:251. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00251

Overarching principles for patient involvement throughout the medicines research and development process

The European Patients’ Academy (EUPATI) is a pan-European Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) project of 33 organisations with partners from patient organisations, universities, not-for-profit organisations, and pharmaceutical companies. Throughout EUPATI the term ‘patient’ references all age groups across conditions. EUPATI does not focus on disease-specific issues or therapies, but on process of medicines development in general. Indication-specific information, age-specific or specific medicine interventions are beyond the scope of EUPATI and are the remit of health professionals as well as patient organisations. To find out more visit eupati.eu.

The great majority of experts involved in the development and evaluation of medicines are scientists working both in the private and public sector. There is an increasing need to draw on patient knowledge and experience in order to understand what it is like to live with a specific condition, how care is administered and the day-to-day use of medicines. This input helps to improve discovery, development, and evaluation of new effective medicines.

Structured interaction between patients of all age groups and across conditions, their representatives and other stakeholders is necessary and allows the exchange of information and constructive dialogue at national and European level where the views from users of medicines can and should be considered. It is important to take into account that healthcare systems as well as practices and legislation might differ.

We recommend close cooperation and partnership between the various stakeholders including healthcare professionals’ organisations, contract research organisations, patients’ and consumers’ organisations*, academia, scientific and academic societies, regulatory authorities and health technology assessment (HTA) bodies and the pharmaceutical industry. Experience to date demonstrates that the involvement of patients has resulted in increased transparency, trust and mutual respect between them and other stakeholders. It is acknowledged that the patients’ contribution to the discovery, development and evaluation of medicines enriches the quality of the evidence and opinion available.[1]

Existing codes of practice for patient involvement with various stakeholders do not comprehensively cover the full scope of research and development (R&D). The EUPATI guidance documents aim to support the integration of patient involvement across the entire process of medicines research and development.

These guidance documents are not intended to be prescriptive and will not give detailed step-by-step advice.

EUPATI has developed these guidance documents for all stakeholders aiming to interact with patients on medicines research and development (R&D). Users may deviate from this guidance according to specific circumstances, national legislation or the unique needs of each interaction. This guidance should be adapted for individual requirements using best professional judgment.

There are four separate guidance documents covering patient involvement in:

- Pharmaceutical industry-led medicines R&D

- Ethics committees

- Regulatory authorities

- Health technology assessment (HTA).

Each guidance suggests areas where at present there are opportunities for patient involvement. This guidance should be periodically reviewed and revised to reflect evolution.

This guidance covers patient involvement in ethical review of clinical trials.

The following values are recognised in the guidance, and worked towards through the adoption of the suggested working practices (section 8). The values are:

| Relevance | Patients have knowledge, perspectives and experiences that are unique and contribute to ethical deliberations. |

| Fairness | Patients have the same rights to contribute to the ethical review of clinical trials as other stakeholders and have access to knowledge and experiences that enable effective engagement. |

| Equity | Patient involvement in the ethical review process contributes to equity by seeking to understand the diverse needs of patients with particular health issues, balanced against the requirements of the industry. |

| Capacity building | Patient involvement processes address barriers to involving patients in ethical reviews and build capacity for patients and ethics committees to work together. |

All subsequently developed guidance should be aligned with existing national legislation covering interactions as stated in the four EUPATI guidance documents.

Disclaimer

EUPATI has developed this guidance for all stakeholders aiming to interact with patients on medicines research and development (R&D) throughout the medicines R&D lifecycle.

These guidance documents are not intended to be prescriptive and will not give detailed step-by-step advice. This guidance should be used according to specific circumstances, national legislation or the unique needs of each interaction. This guidance should be adapted for individual requirements using best professional judgment.

Where this guidance offers advice on legal issues, it is not offered as a definitive legal interpretation and is not a substitute for formal legal advice. If formal advice is required, involved stakeholders should consult their respective legal department if available, or seek legal advice from competent sources.

EUPATI will in no event be responsible for any outcomes of any nature resulting from the use of this guidance.

The EUPATI project received support from the Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking under grant agreement n° 115334, resources of which are composed of financial contribution from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) and EFPIA companies.

Introduction to patient involvement in ethical review

To ensure optimal benefit for patients from a new medicine, and resulting commercial success, pharma companies focus the selection of compounds to develop and the definition of relevant research outcomes around the needs of patients with the respective disease. “Patient centricity” is a rapidly evolving and increasingly important element of pharma companies’ business models. It requires new strategies, new organisational structures, and culture change across the pharma sector. It requires partnership with patient experts who are capable of providing advice on the value of treatments and on what health outcomes are relevant to patients. However, the concept of patient centricity is also relevant for other stakeholders in the medicines development process, especially for research ethics committees who advocate for the protection of patients in clinical trials.

Good clinical trial design is both ethical and scientifically sound. Design decisions include whether the new medicine is to be compared to another medicine or a placebo, how study participants should be selected, and what kind of tests and assessments are to be made (and how often). The risk of potentially harmful side effects needs to be balanced against the potential benefits for the patients taking part, such as early access to a new medicine, more intense diagnostics and supervision, and the chance to contribute to the development of new treatments for other patients with the same disease. Patients’ judgements about such risks and benefits might be different to that of researchers: for instance, depending on the severity of the disease in question, they might be prepared to take a higher risk concerning potential side effects. In today’s practice, the involvement of patients in these decisions is not standard – neither in clinical trials initiated by pharmaceutical or biotechnology companies nor in those initiated by academic institutions.

Clinical trials are subject to a framework of very strict laws. Before a clinical trial can start it needs approval from the competent authority which must ensure that all legal conditions are fulfilled, that the trial is scientifically sound, that the study medication is of proven quality and safe based on preclinical and – if available – previous clinical evidence; and that there is a favourable balance between expected benefits and risks. In parallel to the review by the national competent authority, one or more multi-disciplinary (research) ethics committees review the study protocol and related documents in order to safeguard the study participants. They ensure that the information to patients is comprehensive and understandable. They assess the balance between benefits and risks, ensure that this balance is acceptable, and that the trial is scientifically relevant for patients with the disease in question.

In most European countries patients, carers or patient representatives are only marginally or not at all involved in the ethical and scientific review of clinical trials. In the national legislation of most European countries as well as in the new EU Clinical Trial Regulation (Regulation (EU) 536/2014) the involvement of patients in the definition of the ethical conditions for clinical trials and in the review provided by ethics committees is not clearly defined. The regulation states: “When determining the appropriate body or bodies (i.e. ethics committees), involved in application assessments, Member States should ensure the involvement of laypersons, in particular patients or patients’ organisations.”[2]

While patient involvement in R&D is a more and more accepted concept in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industry, patient involvement in ethics committees is much disputed. Ethics committees are expert advisory groups providing advice on the ethical acceptability of research projects carried out in human beings. They have an obligation to the public to protect the research participants. To fulfil these obligations, ethics committee members need to be independent, neutral, objective and competent in scientific, ethical and methodological topics. The inclusion of a lay member is supposed to support this neutrality and to enlarge the scope of advice. Adding patient members to an ethics committee means a paradigm shift: the patient who represents those who will ultimately benefit from the research sits at the table, may – as a concerned party – overestimate the benefit or underestimate the risks in trial participation. However, the considerations underlying the concept of “patient centricity” in R&D are likely to also apply here: the outcome can be improved if the concerned party can provide their expert input. There is a need for a generally accepted guidance outlining the conditions for collaboration of ethics committees and patients in ethical review.

Scope

This guidance has been developed by the European Patient Academy on Therapeutic Innovation (EUPATI) for all stakeholders in medicines development involved in the ethical review of clinical research projects, with special emphasis on members of research ethics committees and patients/carers or patient representatives providing patient input.

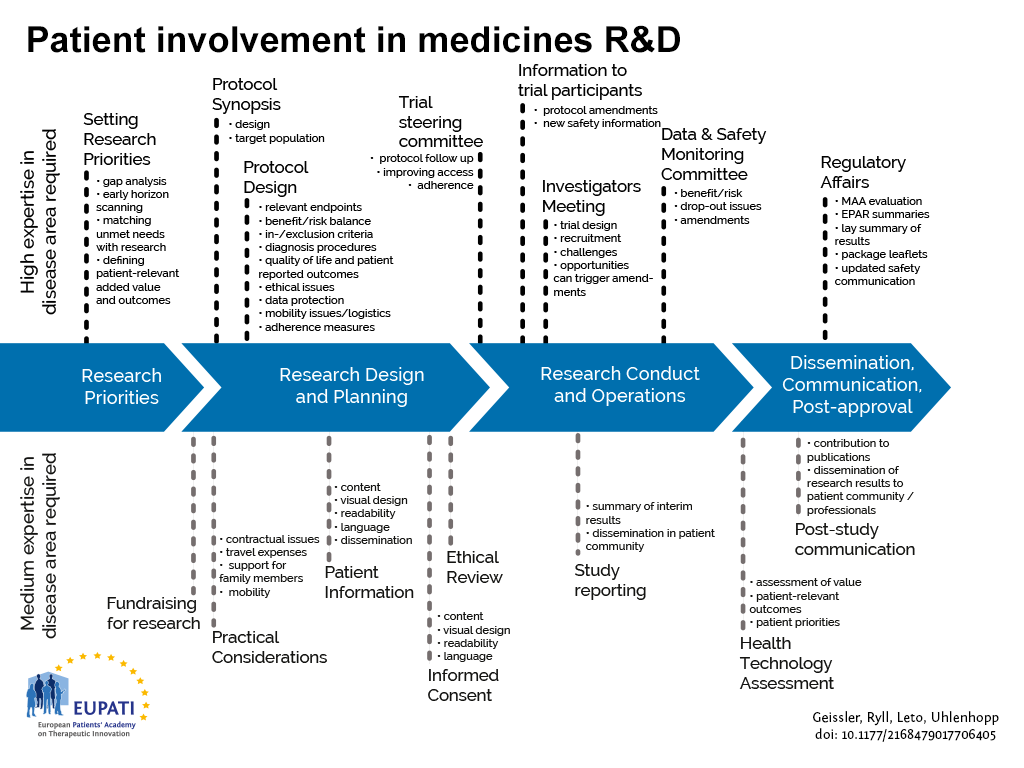

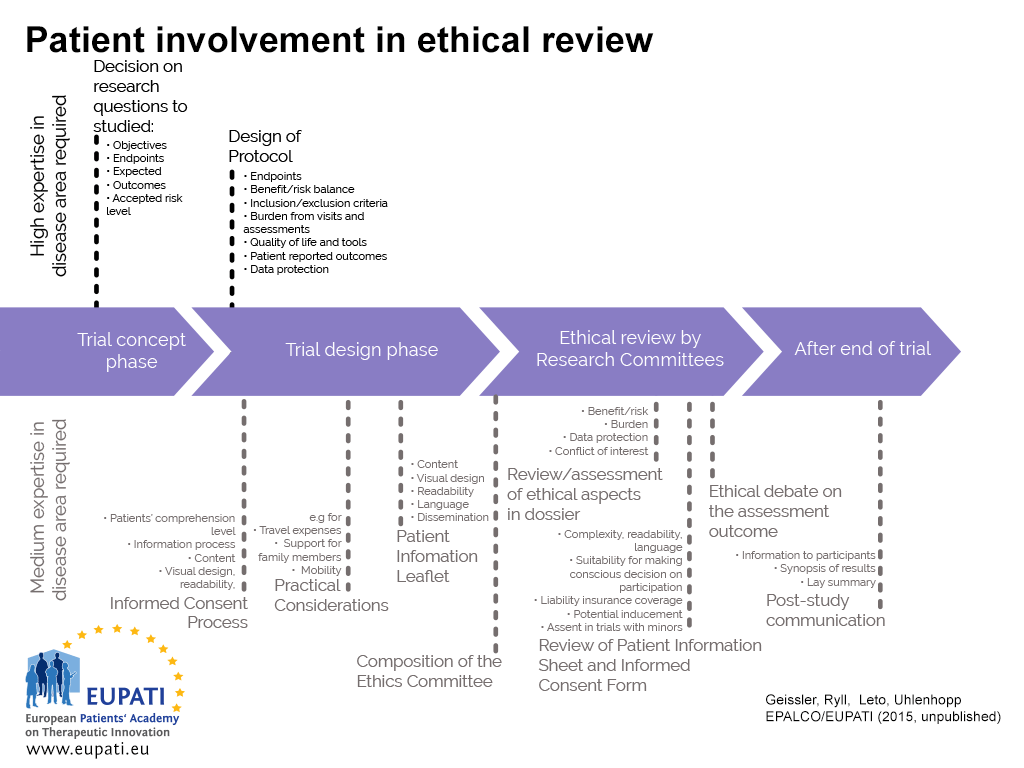

This guidance covers patient involvement in ethical review of clinical trials. Ethical aspects need to be considered in any step of the clinical trial– from definition of the research questions and protocol conditions, to informed consent preparation, to ethical review by ethics committees and to provision of information on trial results to the public. See Figure 1 and 2. This guidance covers patient involvement in any of these steps, although special emphasis is given to patient involvement in research ethics committees.

This guidance is based on the discussions and conclusions from a multi-stakeholder roundtable discussion and a webinar on patient involvement organised by EUPATI, contributions from national ethics committees, consultation within the EUPATI consortium and a comprehensive external consultation process.

- Patients can be involved across the process of medicines R&D. This diagram created by Geissler, Ryll, Leto, and Uhlenhopp identifies some existing areas in which patients are involved in the process. It distinguishes between the level of expertise in a disease area that is required and the different areas where involvement can take place.

- A roadmap of where patient involvement may occur in ethical review

Defining “patient”

The term “patient” is often used as a general, imprecise term that does not reflect the different types of input and experience required from patients, patient advocates and patient organisations in different collaborative processes.

In order to clarify terminology for potential roles of patient interaction presented in this and the other EUPATI guidance documents, we use the term “patient” which covers the following definitions:

- “Individual Patients” are persons with personal experience of living with a disease. They may or may not have technical knowledge in R&D or regulatory processes, but their main role is to contribute with their subjective disease and treatment experience.

- “Carers” are persons supporting individual patients such as family members as well as paid or volunteer helpers.

- “Patient Advocates” are persons who have the insight and experience in supporting a larger population of patients living with a specific disease. They may or may not be affiliated with an organisation.

- “Patient Organisation Representatives” are persons who are mandated to represent and express the collective views of a patient organisation on a specific issue or disease area.

- “Patient Experts”, in addition to disease-specific expertise, have the technical knowledge in R&D and/or regulatory affairs through training or experience, for example EUPATI Fellows who have been trained by EUPATI on the full spectrum of medicines R&D.

There may be reservations about involving individual patients in collaborative activities with stakeholders on grounds that their input will be subjective and open to criticism. However, EUPATI, in line with regulatory authorities, instils the value of equity by not excluding the involvement of individuals. It should be left to the discretion of the organisation/s initiating the interaction to choose the most adequate patient representation in terms of which type of patient for which activity (see section 7). Where an individual patient will be engaged it is suggested that the relevant patient organisation, where one exists, be informed and/or consulted to provide support and/or advice.

The type of input and mandate of the involved person should be agreed in any collaborative process prior to engagement.

Current status of patient involvement in ethical review

Best practice examples have shown that patient involvement in ethical considerations concerning clinical trials as early as in the trial design and protocol preparation stage can be beneficial to strengthen the awareness about ethical issues in the research project. Involvement at this stage can ensure that the focus on the patient is maximised and the outcomes to be measured are relevant to patients. Guidance on this interaction is provided by the EUPATI “Guidance on patient involvement in industry-led medicines R&D”[3]. Similarly, in clinical trials being driven by academia, patient experts could provide meaningful advice.

At the time of ethical review of the clinical trial by the ethics committee, the protocol details have been decided. Focus of this review is the acceptability of the specific benefit-risk balance, the patient protection elements and research site qualification as well as the information to patients during the informed consent process, by ethics committee members bringing in their respective expertise. The addition of patients’ specific expertise can be a relevant expansion of a committee’s expertise.

While participation of at least one lay person in ethics committees is longstanding practice and of undisputed value, the type and extent of patient involvement varies widely between - and even within - European member states. In some countries patient representation is required by law and the conditions are clearly defined. In other countries individual ethics committees are just beginning to implement patient involvement within the frame of their statutes’ flexibility on committee composition or because the law leaves it to the ethics committee to decide if they will involve a lay person or a patient representative. Different practices exist for the following reasons:

- Although there is appreciation of the benefit of patient involvement there is no agreement on the role and most suitable patient profile: patient expert, patient advocate, patient organisation representative or individual patient.

- Finding patients willing to contribute to the ethical review is a challenge for ethics committees, and this is the case across Europe. There is no established match-making process.

- Involving patients with specific diseases can be logistically challenging, while involving patients who advise on all kinds of diseases requires a level of knowledge beyond their personal disease.

- There is disagreement about how far patients with a particular disease can and want to be representative for other patients with this disease, and whether there is potential for bias because of their personal interests. The independence of representatives from patient organisations has been questioned on the grounds that their personal interests and financial support from the pharmaceutical industry might lead to conflicts of interest.

- Pan-European capacity of suitable patient experts is currently scarce.

So far a limited number of patient organisations decided to make efforts to identify and educate individual members for a role with relevant contributions in ethical review and specifically in an ethics committee.

As of 2018, the approval and performance of clinical trials will be governed by the European Clinical Trial Regulation 536/2014. Involvement of patients in the ethical review process is not stipulated in this Regulation, although the legislation states that lay persons, in particular patients or patients’ organisations, should be involved in the assessment of the clinical trial authorisation application. The assessment process and the make-up of the assessing bodies (national competent authorities and ethics committees) are subject to national legislation, consequently the involvement of patients in the ethical review process will continue to vary from country to country.

Timing and nature patient involvement in ethical review

Patients can be involved in the ethical review of clinical trials at different time points (section 4):

- Trial Concept Phase (handled by commercial or academic sponsor)

- Trial Design Phase (handled by commercial or academic sponsor)

- Ethical Review Phase (handled by ethics committee(s))

- After End of Trial (handled by commercial or academic sponsor)

In the Trial Concept Phase patient experts can advise on ethical aspects of the trial such as:

- assessment of preclinical data and/or background evidence

- research questions, e.g., for specific indications, patient populations, etc.

- defining the objectives of the trial to ensure its relevance for patients

- inclusion and exclusion criteria of trial participants

- acceptable/relevant endpoints

- the suitability of measurements and assessments, e.g., quality of life questionnaires and Patient Reported Outcomes

- comparators (placebo or active comparator) and their acceptability for participants

- acceptable risk levels: patients might have a specific opinion on the level of risk they are prepared to accept

We recommend that patient experts should be involved in the Trial Concept Phase - whether a trial is being run by a company or academic centre - to optimise the scientific value of the trial and its viability.

In the Trial Design Phase patient experts can advise on the specifics of the clinical trial that need to be defined in such a way that:

- a suitable number of participants can be recruited in an acceptable time frame,

- the benefits of trial participation outweigh the risks,

- the burden to participants is acceptable,

- the care provided to participants is adequate,

- administration of the trial medication is as easy and reliable as possible,

- measurements and assessments are practical, acceptable to participants and reliable.

- patients will be informed of the trial results, even if stopped early

- the communities where the trial is performed will benefit from its results

Although patients can provide valuable input in many other aspects, a typical area of patient involvement in this phase is the development of the informed consent process including the preparation of the patient information sheet and informed consent form. Input from the kind of patient that these documents are developed for can improve their readability, user-friendliness and completeness.

We recommend that patient experts should be involved in the Trial Design Phase - whether a trial is being sponsored by a company or academic centre, to support the acceptability of the trial conditions for participants and the relevance of its outcome for the respective patient community.

In the Ethical Review Phase, performed by one or more ethics committees, patient experts or patient advocates can provide important input into the elements described above. In addition, patients can advise on local conditions for the trial such as:

- assessment of the benefit/risk balance

- fairness of inclusion and exclusion criteria

- suitability of patient liability coverage (insurance)

- data protection measures

- potential conflicts of interest

- readability and acceptability of the informed consent documentation

- avoidance of inducement, for example ensuring that patient fees or travel expenses are appropriate

- how patient organisations can contribute to the patient information and recruitment processes

We recommend that patient experts, patient organisation representatives or patient advocates who are knowledgeable about living with the disease in question should be involved in the review of clinical trials provided by ethics committees, to support trial participants’ optimal protection.

Sponsors sometimes involve patients in communication with trial participants after the end of the trial, but this has been very limited in the past. Under the new Clinical Trial Regulation, however, the results of every clinical trial will have to be communicated in a lay summary, to ensure transparency and to recognise the patient community’s contribution to the trial. Patient input to lay summaries will be essential to ensure they are suitable and readable for patients.

We recommend that commercial/academic sponsors involve patient experts or patient organisation representatives, knowledgeable about living with the disease in question, in the development of lay summaries to ensure they are non-biased, suitable and readable for patients.

Practical aspects of patient involvement in ethics committees

National legislation outlines the constitution, organisation and responsibilities of ethics committees, and reflects the roles of different types of ethics committees in the protection of trial participants and research integrity.

Different roles for patients in ethics committees can be considered:

- Full member of an ethics committee with equal rights and obligations as all other members

- External peer reviewer giving advice to the ethics committee members before their review meeting

The specific process for selection of the members of an ethics committee varies between countries and are defined by national legislation, responsible professional bodies or the ethics committee’s own standard operating procedures.

Patients’ level of expertise

Ethics committees should make a reasoned decision on the level of expertise they expect from their patient member(s):

- “Individual patients” with the disease in question, parents or carers of those patients, can provide valuable input to the patient information sheet and informed consent/assent form with a view from outside and can comment on aspects of a trial that will affect quality of life and the burden for participants. However, after some months of experience they might not be research-naïve anymore and it is argued that this could affect the value of their input. It can be difficult for research-naive patients to take part in discussion of other ethical topics that involve scientific and/or methodological complexity. The contributions of research-naïve patients without experience of the disease in question could be seen as comparable to those of lay persons.

- “Patient advocates” have an in-depth knowledge of living with the disease from their own experience and might have a level of understanding of research and medicines development for this disease. With each ethical review project they gain additional experience. The representativeness of their advice, however, might be limited by lack of in depth knowledge about cases beyond their own and perhaps a few other cases. Their contribution to ethical review of trials for other diseases will be limited to a general patient perspective.

- “Patient organisation representatives” are either patient with the disease in question and/or actively engaged in a relevant patient organisation and are exposed to the disease experience of many individuals. They are knowledgeable about the needs, desires and opinions of this community and thus will be relatively representative. Since patient organisations exist to support their members and to lobby for their interests it is important to ensure that the patient organisation representative in the ethics committee is aware of his/her obligation to provide un-biased advice. Their contribution to ethical review of trials for other diseases will be limited to a general patient organisation perspective.

- “Patient experts” (e.g., EUPATI Fellows) have personal experience of living with the disease and/or the combined knowledge from working with members of their patient organisation. In addition, they have a comprehensive understanding of all aspects of the medicines development process, and can actively participate in all aspects of the ethical debate on the same level as the other ethics committee members. They are not joining the ethics committee in a representative role but have much exposure to other cases due to their activities in their patient organisation. Their contribution to ethical review of trials for other diseases could also be valuable because of their knowledge of R&D.

We recommend that patient experts, patient advocates or patient organisation representatives knowledgeable about living with the disease in question should be involved in the work of research ethics committees, preferably as full members, to extend their input beyond development of the patient information sheet and informed consent form.

Finding supportive patients and interested ethics committees

Ethics committees report that it is difficult to find patients willing to participate, and in particular to find patients with the expected level of expertise. Involvement of a “generic” patient representative reviewing trials for all kinds of diseases makes finding patient members easier but this has disadvantages as described above. Identifying patient members for specific diseases and bringing them to ethics committee meetings can be a logistical challenge. However, patients can participate in ethics committee meetings via tele- or web-conference. Alternatively, patients can be asked to provide their written comments before the ethics committee meeting but this means that the impact of patients on the ethical debate during the meeting is missed.

There are a number of options for ethics committees to identify interested patients and for interested patients to join an ethics committee:

- Ethics committees can stablish collaboration and enable ethical review education opportunities with (umbrella-) patient organisations

- Advertisement

- Use of existing contacts

- Unsolicited applications from patients

- Supporting the development of a national match-making platform jointly with academic and commercial sponsors to facilitate collaboration with interested patients with different diseases and different levels of expertise.

We recommend that individual ethics committees develop a database of patients willing to join the ethical review process and we encourage ethics committees to join forces to establish a joint database, e.g., on national or regional level.

We recommend that patient organisations create a database of members interested and educated in ethical review of clinical trials. Patient organisations should communicate the existence of this database to the national ethics committees.

Conditions for patient involvement in ethics committees

The conditions for patient involvement in the work of an ethics committee should be communicated to interested patients or patient representatives to ensure smooth and efficient collaboration.

Written agreement

A written agreement should be signed by both parties containing a clear description of the role of the patient in the ethical review process. The agreement should specify the legal and regulatory conditions, working procedures, ground rules and conflict resolution procedures, frequencies of interaction, mutual obligations including confidentiality, liability (insurance) protection, resource requirements and timelines as well as the mechanism for payment / reimbursement of expenses and any other benefits.

To ensure clarity about the collaboration between ethics committees and participating patients we recommend signing a written agreement before the start of the collaboration.

Transparency

As with all members of an ethics committee, patient members in ethics committees should ensure they are transparent about their own (and/or their patient organisation’s) professional interests and financial support.

We recommend that patient members should sign the same Declaration of Interest as the other ethics committee members, to list potential conflicts of interest such as professional involvement and financial interests in other organisations and personal and professional (if the patient is a patient organisation representative) funding sources.

Representativeness

Representativeness of the patient members’ advice is an important aspect for both the ethics committee and the patient community they are representing. Only a limited number of patient organisations have systematically compiled information relevant for the ethical review of a clinical trial in their area of indication and decided on a member interested and suitable to represent the organisation in an ethics committee.

We recommend that patient organisations identify members interested in representing the organisation in an ethics committee and ensure that these members receive comprehensive information about the community’s treatment needs, quality of life deficiencies, and day-to-day life conditions.

We recommend that patient organisations implement a mechanism to exchange experiences which their members develop in ethics committees while respecting the patient members’ confidentiality obligations.

Appointment, introduction and training

The appointment process and introduction of patient members should follow the standard rules of the respective ethics committee.

Participating in the ethical review in an ethics committee is for many patients and patient organisation representatives a new experience. Debating with experts in their field might be intimidating and can lead to a lack of contributions: it is important that the mere presence of patient representation is not seen as a given endorsement to committee decisions. To support real engagement, the capacity of patients experienced in providing advice to ethics committees needs to be systematically increased. This should include a comprehensive introduction into the work of an ethics committee member and continuous professional development initiatives, even if his/her involvement is limited to contributions relevant to their disease area.

We recommend that patient members receive a comprehensive introduction and appropriate continuous training independent of the frequency of their participation in ethical review.

Compensation

It should be recognised that in many situations patients involved in activities do so voluntarily either as an individual but also when a member of an organisation. Consideration should therefore be given to:

- compensate for their total time invested plus expenses

- any compensation offered should be fair and appropriate for the type of engagement. Ideally travel costs would be paid directly by the organising partner, rather than being reimbursed.

- covering the costs incurred by patient organizations when identifying or supporting patients for involvement in activities (i.e peer support groups, training and preparation) should also be considered.

- help organise the logistics of patient participation, including travel and/or accommodation.

Compensation also includes indirect benefits in kind (such as a patient organisation providing services free of charge) or any other non-financial benefits in kind provided to the patient/patient organisation (such as training sessions, the setting up of web sites).

All parties should be transparent about any compensation arrangements.

References

- Adapted from the EMA framework. European Medicines Agency (2022). EMA/649909/2021 Adopted. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/engagement-framework-european-medicines-agency-and-patients-consumers-and-their-organisations_en.pdf. Last Accessed 12 February 2024.

- EU Regulation on clinical trials on medicinal products for human use No. 536/2014. (2014) https://ec.europa.eu/health/human-use/clinical-trials/regulation_en. Last Accessed 6 July, 2021

- EUPATI Guidance on Patient Involvement in industry-led medicines R&D (2016). https://toolbox.eupati.eu/resources/guidance-for-patient-involvement-in-industry-led-medicines-rd/ Last Accessed 6 July, 2021.

*Consumers are recognised as stakeholders in the healthcare dialogue. The scope of EUPATI focuses on patients rather than consumers this is reflected in the educational material and guidance documents.

Attachments

- EUPATI Guidance for patient involvement in ethical review of clinical trials-EN-v1

Size: 297,096 bytes, Format: .pdf

EUPATI guidance on patient involvement in ethical review Version 1 English